En ce début d’année, l’heure est au bilan. On se repasse le film à l’envers, on classe, on garde, on jette, un peu comme on se débarrasserait d’une ancienne peau, avec l’espoir inavoué que nouvelle année va rimer avec nouvelle vie, ou tout au moins avec vie meilleure, plus ceci ou plus cela.

En ce début d’année, l’heure est au bilan. On se repasse le film à l’envers, on classe, on garde, on jette, un peu comme on se débarrasserait d’une ancienne peau, avec l’espoir inavoué que nouvelle année va rimer avec nouvelle vie, ou tout au moins avec vie meilleure, plus ceci ou plus cela.

Les vélos pliants sont une belle alternative pour des utilisations urbaines, de loisirs, en bord de mer. Compact et léger, il ne prendra pas de place dans votre coffre de voiture, placard , ou dans la caravane.

Plusieurs d’entre vous se sont livrés courageusement au jeu du classement, exercice auquel je suis incapable de me frotter.

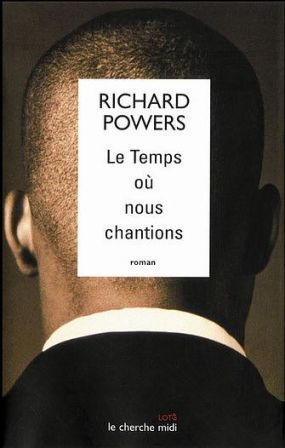

Toutefois, parmi mes lectures 2006, un roman sort du lot, laissant loin derrière tous les autres, les excellents comme les plus anodins, qui a trusté de longues semaines la rubrique Coup de cœur de ce blog et qui y figurerait encore certainement si je ne m’étais forcé à l’en déloger : Le Temps où nous chantions, de Richard Powers.

Je ne suis pas le seul à m’être laissé captiver par Le Temps où nous chantions. Chimère, Cuné, Papillon et Sophie vous ont également dit tout le bien qu’elles pensaient de ce roman hors catégorie.

Alors pour commencer l’année en beauté, plutôt que de tourner la page, faisons un arrêt sur image pour faire durer le plaisir. Voici donc un long extrait de The time of our singing lu par l’auteur himself, ainsi que la transcription d’une interview que Richard Powers a accordé au magazine Chronic’Art lors de la sortie de son roman en France.

Histoire de vous mettre l’eau à la bouche, en attendant sa traduction en français (qui ne devrait pas se faire trop attendre vu le succès rencontré par Le Temps où nous chantions), voici un court extrait du nouveau roman de Richard Powers, The Echo maker, récompensé par le prestigieux National Book Award.

Dans ce roman qui se déroule au temps des grandes migrations, un jeune homme victime d’un accident de voiture est atteint d’un trouble neurologique rare (le syndrome Capgras) à cause duquel il ne reconnaît plus ses proches qu’il prend pour des imposteurs…

Part One

Cranes keep landing as night falls. Ribbons of them roll down, slack against the sky. They float in from all compass points, in kettles of a dozen, dropping with the dusk. Scores of Grus canadensis settle on the thawing river. They gather on the island flats, grazing, beating their wings, trumpeting: the advance wave of a mass evacuation. More birds land by the minute, the air red with calls.

A neck stretches long; legs drape behind. Wings curl forward, the length of a man. Spread like fingers, primaries tip the bird into the wind’s plane. The blood-red head bows and the wings sweep together, a cloaked priest giving benediction. Tail cups and belly buckles, surprised by the upsurge of ground. Legs kick out, their backward knees flapping like broken landing gear. Another bird plummets and stumbles forward, fighting for a spot in the packed staging ground along those few miles of water still clear and wide enough to pass as safe.

Twilight comes early, as it will for a few more weeks. The sky, ice blue through the encroaching willows and cottonwoods, flares up, a brief rose, before collapsing to indigo. Late February on the Platte, and the night’s chill haze hangs over this river, frosting the stubble from last fall that still fills the bordering fields. The nervous birds, tall as children, crowd together wing by wing on this stretch of river, one that they’ve learned to find by memory.

They converge on the river at winter’s end as they have for eons, carpeting the wetlands. In this light, something saurian still clings to them: the oldest flying things on earth, one stutter-step away from pterodactyls. As darkness falls for real, it’s a beginner’s world again, the same evening as that day sixty million years ago when this migration began.

Copyright © 2006 by Richard Powers.

Published in October 2006 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. All rights reserved